Meet Malcolm Reid: The shortest player in Division I basketball

Malcolm Reid knows he'll draw attention each and every time he emerges from the tunnel. The Southeastern Louisiana walk-on guard will be met at opposing arenas with raised eyebrows, a few chuckles and an occasional verbal jab.

The stares are second nature, as are the chants. He’s heard them all before.

Nothing has been able to derail him. Not a doctor’s diagnosis as an infant. Not the time he was snubbed from the freshman team in high school. And certainly not the countless looks and laughs he’s received over the years.

Malcolm Reid is 5-foot-2, and he is the shortest player in Division I basketball.

**********

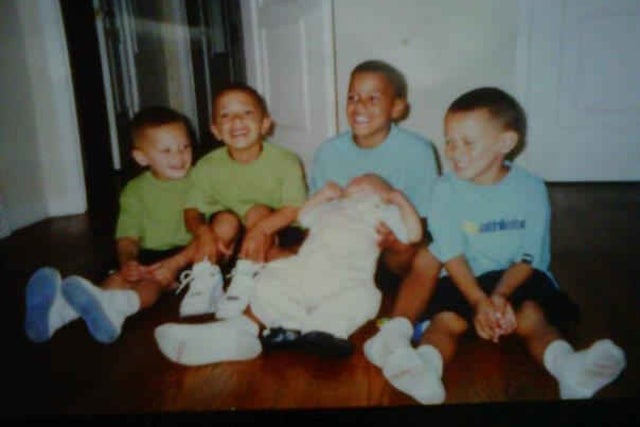

Malcolm was born in Reims, France, the second of five sons. His parents, Billy and Laurence, met in France during his father's overseas pro career. When Malcolm was two months old, doctors informed them that their son was born with a condition called hypochondroplasia, a disorder that results in shorter limbs. He was bow-legged, his hips were out of line. He would never walk.

But for dad Billy Reid, who overcame the odds of growing up in the South Bronx, and ended up being the last pick in the 1980 NBA Draft — when the draft went nine rounds — this was not an option.

“Of course, me being the way I was as far as work ethic, I said, ‘No, that’s not going to happen. He’s going to walk,’” Billy said.

“We would always sit him up against the couch for a while. It went from that sit up position to then standing up," Billy continued. "Then he started walking, and just like other kids, he would walk and fall. He kept making progress and kept making progress, and that’s why he does what he does now.”

The same ethic applied to basketball.

As a freshman at Oak Grove High School in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, Reid was cut from the freshman basketball team. When he approached the coach to ask why, he was met with a familiar line.

“He told me I was too small to play,” Reid said.

When Malcolm saw his older brother, William, and other players prepare for practice, it was his cue to run off to Southern Miss, where his father was a member of Larry Eustachy’s coaching staff, and conduct a practice of his own.

“Who better to tell Malcolm that you can be the underdog? I told him, ‘If you put the work in, something can come out of it. All those guys were picked ahead of me and I still made the NBA,’” said Billy, who played for the Golden State Warriors.

Billy had helped Malcolm learn to walk. That year of individual practice began with Billy teaching his son how to run. Because of his shortened limbs, he would swing his legs out to the side when he ran. He would run up and down the stadium steps at Reed Green Coliseum to correct his form. Malcolm would also put himself through extensive dribbling exercises to go with his increased speed.

“My dad taught me how to handle the ball with a machine gun dribble, figure eights, cone drills.” Malcolm said. “Everything possible. I would look up things on the Internet. I just did everything that I could.”

The following year, Billy stepped away from college coaching and moved from Hattiesburg to Diamondhead on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. William and Malcolm attended St. Stanislaus College, an all-boys prep school in Bay St. Louis. William made varsity, while Billy joined the program as an assistant coach. But the move to St. Stanislaus also gave Malcolm a chance to play, making JV and suiting up for varsity as a sophomore.

“Obviously, he was a hard worker,” former St. Stanislaus head coach Jay Ladner recalled. “He’s extremely small, but what I admired about him was his tenacity, heart and great attitude.”

Ladner left to coach Oak Grove, of all places, following the 2010-11 season. Malcolm was entering his senior year, and when Ricky Stone, another legendary area high school coach, arrived to replace Ladner, he named Malcolm captain. He would average 7.9 points per game in his final season and drew interest from several colleges.

But an ACT score kept him from attending Spring Hill College, a NAIA school in Mobile, Ala., which is considered one of the best liberal arts schools in the South.

So Reid ended up spending a year at Jones County Junior College in Ellisville, Miss., a two-hour drive from where his father lived. Ladner was also at Jones, beginning his first season as the school's head coach.

Malcolm did not play at Jones, deciding to focus solely on his academics. He was set to enroll at Spring Hill in the fall of 2013, only to find out the school had parted ways with the coach who had recruited him.

New coaches have no requirements to remain loyal to holdovers, especially ones with Reid’s stature. And Malcolm felt he was failing the eye test once again.

Reid alerted his coach before the team’s first game of the 2013-14 season that he intended to transfer.

“I gave it a shot, but I didn’t feel comfortable,” Reid said. “I talked to him and told him I thought I was doing good in practices and in the scrimmages and felt he was still putting players in front of me.

“He just let me go. And that’s what told me that he didn’t really care.”

By December of 2013, Reid was working at SkyZone, an indoor trampoline park in Suwanee, Ga.. He had relocated to Lawrenceville, a suburb 30 miles northeast of Atlanta, to take a semester off and live with William.

By then, William was Malcolm's only brother still living in the U.S. Malcolm's mother and his three younger brothers had moved back to France.

“I think it was good for him,” William said of Malcolm’s semester off. “We didn’t really get to spend much time with each other because I was in college, too. This was probably a good break for him to spend four or five months with me. We talked about things and worked out together. It was refreshing.”

Unbeknownst to Reid, an opportunity to return to school and basketball was about to emerge.

*******

Jay Ladner’s tenure at Jones County was brief. In his second season, he led the No. 11 seeded Bobcats to a NJCAA Division I national championship, the lowest seed ever to win the title, and the only team to do so by winning five games in five days.

Less than three weeks after the improbable run, Ladner was introduced as Southeastern Louisiana's new head coach.

“Coach Ladner was the same guy who gave me a chance in high school. I know he respects me and I know he respects my game and that he’s always going to push me,” Malcolm said. “That’s why I wanted to come here and be back around him.”

Reid reached out to his former coach and was given an invitation to walk-on — although that would be delayed by a season, as he was ineligible to practice and was required to catch up on the semester he had missed. Reid will have two years of eligibility remaining, spending most of those days on the Lions’ scout team. But the 21-year-old is on the roster.

Many knew what to expect from the diminutive newcomer on the first day of practice, with three players on the roster also from St. Stanislaus and another from rival Gulfport High School.

“You can’t take the ball from him because he’s so low to the ground,” said redshirt freshman Dimi Cook, who played against Reid in high school. “And when he’s on defense, you can’t get by him with just average moves, or he’ll take it from you. He’s annoying in practice and he knows it, too.”

Southeastern Louisiana is picked to finish in the middle of the pack in the Southland Conference. Not bad for the second season of a rebuilding project. Ladner loaded up his non-conference schedule with games against Texas A&M, Cincinnati and Florida State, all-NCAA Tournament-caliber teams. There will likely be moments where Ladner will look to the end of the bench and call Reid’s number. He’ll tighten up his white shoes, remove his warm-up jersey and check into the game. Fans will see his 5-foot-2 frame, small enough to be denied entry on some amusement park rides, but strong enough to win a few arm wrestling contests.

His biceps are covered with tattoos. The word “Strength” runs down the back of his right arm, the word “Family” written on the inside of his left. The phrase, "Sky is the Limit" is tattooed on his left arm above a cross, which includes his parents’ names and brothers’ initials. But the one tattoo fans won’t see is the one that best describes him. It’s a quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson, inked across his chest, running right over his heart.

“Our greatest glory is not in never failing, but in rising up every time we fail.”