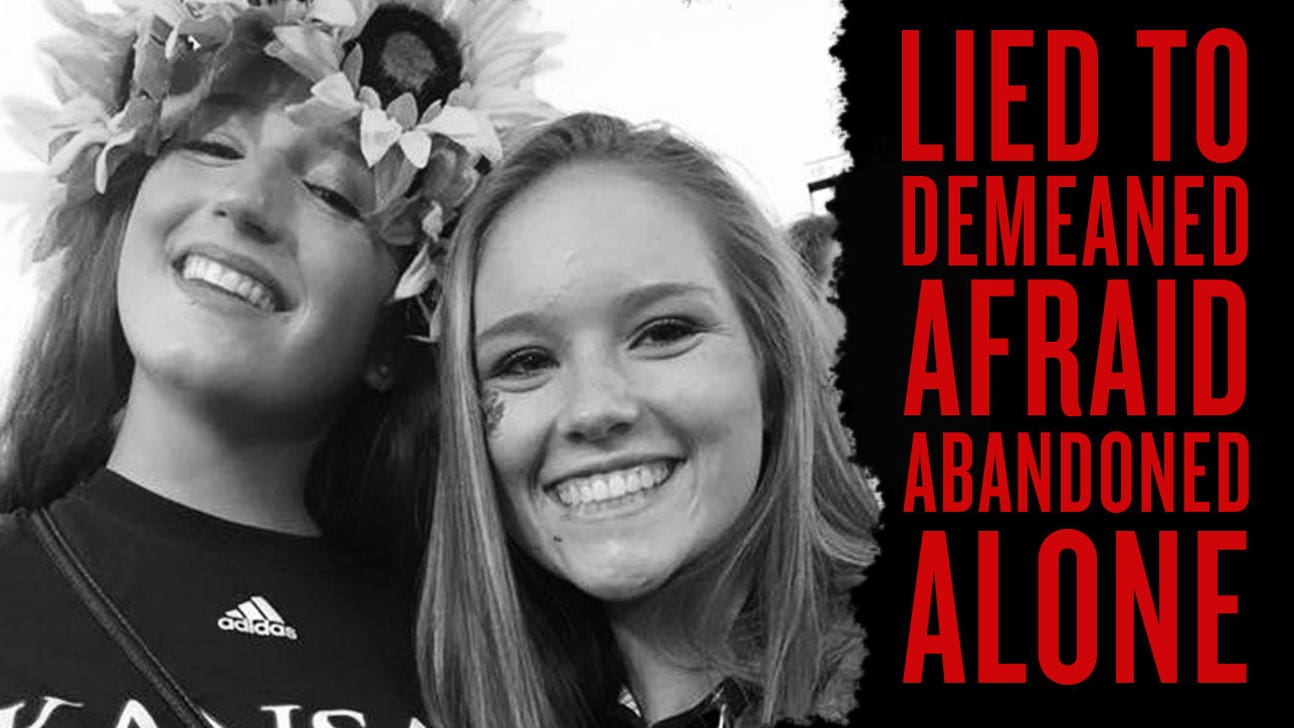

Two ex-Kansas rowers accused a football player of sexual assault. They feel the university failed them.

After being on the University of Kansas campus for less than a week in August 2015, scholarship freshman rower Sarah McClure says a football player sexually assaulted her. McClure, then an 18-year-old from Chicago, minces no words, describing her life since then as nothing short of a living hell.

The constant fear. The cold sweats. Afraid for other women who might come into contact with her assailant. A 24-hour reminder of a nightmare playing in her head, hoping to wake up and realize this is not a dream.

“I am miserable. I have PTSD. I have a support dog. Not only did that coward take away a piece of me, Kansas did as well,” she says. “I couldn't move. I couldn't move for days. I cried for days.”

Ten months earlier another female rower, Daisy Tackett, says the same football player sexually assaulted her following a Halloween party on Nov. 7, 2014 at Jayhawker Towers, which houses students and athletes at Kansas.

“I am trying my best to move forward,” Tackett says. “Describing what my life has been like since that a--hole attacked me is so difficult. I want him to pay for what he did. It’s not right and I will not stop until something is done.”

In separate lawsuits filed against the University of Kansas, two women tell the same story.

Assaulted. Lied to. Left behind.

The accused football player is identified in University of Kansas Student Affairs records as Jordan Goldenberg and in court documents as John Doe G.

Goldenberg was the Jayhawks’ long snapper for the first seven games of the 2015 season. He has not been criminally charged or named as a defendant in either lawsuit and, through his attorneys, adamantly denied the allegations to SI.com.

The Douglas County, Kansas District Attorney’s office says it received an investigative report from the University of Kansas on McClure’s behalf on Nov. 9, 2015 and two months later prosecutors declined to press charges, citing evidence needed for a conviction is “insufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Despite that, the Institutional Opportunity and Access (IOA) at the University of Kansas continued its investigation of Goldenberg. Before a hearing could be conducted to see if Goldenberg violated the school’s Code of Student Rights and Responsibilities, he agreed to be expelled from the university in March 2016.

A letter from the University of Kansas Student Affairs office confirms that its IOA office found, following an investigation, that Goldenberg had “non-consensual sex” with Tackett.

A separate letter confirms that the IOA found he violated the school’s Sexual Harassment Policy with McClure.

The IOA recommended that he be “permanently expelled” from the University and, prior to his scheduled hearing, Goldenberg “was willing” to accept this recommendation.

Goldenberg was permanently expelled, ordered to stay away from both women, banned from campus for the next 10 years, and had an undisclosed notation placed on his transcript. Citing privacy laws, Kansas’s officials also declined to comment on the exact language on Goldenberg’s transcript concerning the reason for his expulsion from school.

Goldenberg’s lawyer denied the IOA’s findings, and says his client “withdrew” from Kansas for what he termed “non-academic misconduct, not eligible for reinstatement in lieu of expulsion,” according to what he says are the words in a resolution letter from the school. His lawyer declined to provide this letter to SI.com, or to be named at his client’s request.

In another motion filed earlier this month, McClure is challenging the nature of Goldenberg’s departure from Kansas and claims that Kansas told Goldenberg he could leave the university “in lieu of expulsion” concealing this information from McClure and Tackett out of fear of being sued by Goldenberg.

Goldenberg’s lawyer says he won’t comment further on the case.

Goldenberg again maintained his innocence despite the departure from Kansas. His attorney says his client is not planning on suing anyone for defamation at this point. There have been many questions about Goldenberg’s case and the circumstances surrounding his departure from the school.

A questionable transfer

Goldenberg transferred to Indiana State University, where he promptly joined the football team as a long snapper this past summer. ISU officials said there is no protocol or statute on transfer rules pertaining to any student who has a notation on their transcript as Goldenberg was supposed to have. When asked how and why they admitted Goldenberg to Indiana State, officials could not give a definitive answer, only saying they are conducting a review and are in the process of looking into changing the process for transfers who have been expelled from a previous institution.

Officials also did not disclose what information they found when conducting a review of Goldenberg after several requests from SI, but he is still listed on the school’s directory as being enrolled.

Goldenberg’s former special teams coach at Kansas was Gary Hyman, who left Kansas in February and is currently Indiana State’s special teams coordinator and tight ends coach. Hyman, through Indiana State’s athletic department, declined to comment. Goldenberg was eventually dismissed from the team.

“Jordan Goldenberg Jr. has been removed from the Indiana State University football team, effective Aug. 25,” a statement from Indiana State said. “The upper administration of the athletics department and football team recently learned more information about Goldenberg and after a review, decided it was best for him to focus on obtaining his degree. Steps have been taken to ensure this situation is not repeated. Because of privacy limitations, the University will not release further details.”

Despite being on the Kansas football roster for at least two seasons, Goldenberg was listed on Indiana State’s roster as a freshman on the day before he was dismissed. Indiana State athletic director Sherard Clinkscales says he did not find out about Goldenberg until Aug. 24 after being contacted by SI.

“I didn't know who the person was,” Clinkscales said. “So I had to find out who this person was on the roster."

Less than 24 hours later, Goldenberg was dismissed from the team.

“I can't speak on behalf of anything about the student because of certain HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) Rights. All I can tell you is that I stand behind our statement about our decision as a university and as far as I know, the young man is still a student here pursuing his education,” Clinkscales says.

Clinkscales declined to go into detail about what oversights could have allowed Goldenberg to walk on the football team in the first place.

Hyman, who was Goldenberg's position coach and moved to a non-football role at Kansas at the end of the 2015 season, is the only person who was disciplined relating to Goldenberg's dismissal. The coach received a two-day suspension from the team for his role and did not coach in Indiana State’s season opener against Butler.

Clinkscales declined to answer questions about Hyman and Goldenberg’s relationship from Kansas.

‘This is a case where you know unfortunately things that could have been looked into a bit more. I have taken the appropriate actions that I think that are warranted and kind of go from there,” Clinkscales said.

While the admissions department is separate from the athletic department, there is precedent at Indiana State for allowing student athletes with checkered pasts to participate with the football team. ISU head coach Mike Sanford told the Associated Press last year the school does not require background checks of prospective students after adding ex-Indiana safety Antonio Allen, who the Hoosiers dismissed after his arrest for dealing methamphetamine, heroin and cocaine. Allen left ISU earlier this year and is now enrolled at Marian University, an NAIA program in Indianapolis.

The university's role

After the alleged assaults at Kansas, the women allege that university administrators and the rowing coaches abandoned them in their time of need. At every turn, the two accusers claim, the coaches were complicit in creating a hostile environment of intimidation and ridicule from other members of the rowing team, suffered verbal abuse for the coaches and that Kansas failed them by not providing adequate protection from their attacker.

McClure referred to the treatment of administrators at the school as treating her like “a little lab rat.”

“In order to have any sort of support system, you had to go through a bunch of demeaning people. It was so demeaning that made you feel like you weren’t human,” McClure said. “They did everything in their power to not let me be able to help myself. And not give me any resources that I could ever have. I would always say they made my life a living hell. Over and over and over again.”

SI contacted the Kansas rowing coaches to address the allegations, but they too declined comment.

“We appreciate the opportunity. Since this matter is in litigation, neither (rowing coach) Rob Catloth nor anyone else at Kansas Athletics will make a comment until such time as we deem appropriate,” Jim Marchiony, associate athletics director said in a statement.

McClure, Tackett and their parents have brought a class action lawsuit against the University of Kansas under the Consumer Protection Act and Title IX, a federal statute that prohibits gender discrimination at schools that receive federal funds and allows for the punishment of schools that violate the law. McClure has separately sued the University of Kansas. Goldenberg has not been named as a defendant in either lawsuit.

Petition File Stamped by Gabriel Baumgaertner on Scribd

The Kansas Protection Act protects citizens from deceptive or fraudulent business practices, and in their lawsuit, the Tacketts want the university to stop saying that the dorms on campus are safe.

Tackett and McClure are seeking an actual damages award, attorneys’ fees and return of their tuition and board. They filed an amendment to the lawsuit on Aug. 9, alleging the women’s rowing team was forced to attend home football games and that the school had a policy and practice of “entertaining football recruits in hotels just off campus and encouraging female KU athletes to attend parties with the recruits.”

Kansas spokeswoman Erinn Barcomb-Peterson said the university doesn’t comment on pending litigation, but did not walk back comments made to the Kansas City Star calling the lawsuit “baseless.”

In a motion filed in response to Tackett’s lawsuit, Kansas said the claims have no merit and should be dismissed, and because Goldenberg was expelled, the school adds “those are not the actions of a university that is deliberately indifferent to acts of sexual violence.”

When asked what makes the residence halls safe, Barcomb-Peterson forwarded SI a list of safety amenities provided by Kansas, where a 24-hour staffed main desk is available in the residence halls, but not in scholarship halls or on-campus apartments.

The school stands by claims saying it is confident in the safety on campus, and any suggestion otherwise is not true.

After repeated attempts in asking whether the school can still make claims that the lawsuit is baseless despite their own IOA department and the subsequent investigative report stating that Goldenberg’s actions merited expulsion, the spokeswoman refused comment.

The women’s story

Sexual assault has been and still is an issue that universities across the country have failed to get a handle on.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, among college age females (18-24), 80% of college-aged females who are sexually assaulted knew their attacker and fewer than 20% of female students and non-students received assistance from a victim services agency.

What follows is a look into both women's lawsuits, the role of the school in protecting both women and possible systematic failures of both of Kansas, Indiana State and the Department of Education, that allowed Goldenberg to transfer another university and go virtually undetected for months.

Daisy Tackett always was a big dreamer. A go-getter, not one to give up ambition or listen to people who told her she could not do something.

Tackett grew up in the Dallas area and says she took up rowing in the eighth grade, as her father, aunt and college rowed during their time in college. While attending the Hockaday School, which is a private girls' high school in Dallas, she also excelled on the track team, throwing the discus and shot put.

She moved to Florida during her junior year, but by the time she was set to graduate she had rowing scholarship offers from multiple schools, including Kansas, Duquesne, Tulsa, and Massachusetts. Impressed the most by Kansas during the recruitment process, she decided to make the leap and commit to the school.

“They gave me the impression that they would take care of me,” Tackett said. “I would talk to the coach for five minutes and I felt like they wanted me. That was the lynchpin of my decision.”

Arriving on campus, Tackett decided to fill her time with activities. Along with a full course load and rowing team responsibilities, she decided to join the student senate. But less than three months later, Tackett claims in the lawsuit that she was brutally attacked by Goldenberg following a Halloween party where other attendees were drinking alcohol and doing drugs at Jayhawker Towers, a student dormitory located near the center of campus.

“But nothing can prepare you for what is actually happening and you don't know what to do,” she said. “And you know, yeah I'm a big girl. (5’ 10", 190 lbs.) Yeah, I'm a big rower and I have strength.”

Unsure of what to do or where to go for help, Tackett said she kept quiet, except telling two close friends about the assault. “I was afraid that if I reported it,” Tackett said. “I thought I would get in trouble because I had had a very small amount to drink that night. And at the time it happened there were no protections in place for student athletes that said, 'Hey if I drank and I was assaulted and I want to report it, that I wouldn't lose my scholarship because I was drinking."

The fear took over as the months progressed, and when she finally did report the assault nearly a year later in October 2015, Tackett says she to went the interim campus Title IX coordinator, Joshua Jones, and the university’s IOA. The IOA is a university department, which according to their website, has many functions, including investigating discrimination and harassment complaints.

Multiple attempts to contact Jones and the IOA office at Kansas for comment were unsuccessful.

The school’s previous IOA director, Jane McQueeny resigned the same month Tackett reported her assault to the school. Kansas has been under intense scrutiny since a freshman, who says she was raped in 2013, triggered a Title IX investigation the following year on the school’s response to sexual assault. The school currently has two [sexual assault] cases that are being investigated by the Department of Education.

“And since the assault happened about 11 months prior, I was not aware that there was a statute of limitations on reporting or prosecuting sexual assault in the state of Kansas,” Tackett said.

Or at least that’s what she believed.

Tackett claims the officials at the IOA told her she had one year to file a sexual assault complaint and when she went to the department for help in doing that, she says they were no help at all.

In the state of Kansas, criminal charges for aggravated criminal sodomy, murder, terrorism, or illegal use of weapons of mass destruction are the only crimes can be filed at any time. Every other crime under Kansas law has a five-year statute of limitations, says Cheryl Wright-Kunard, an assistant to the district attorney in Douglas County, the same jurisdiction that declined to press charges in the McClure case.

No one from the IOA returned SI’s calls for comment in regards to this specific allegation.

Fed up with the process, Tackett says she decided to stick it out at Kansas, but the harassment continued.

“They claim they will help you with like parking passes if you need to park closer to your classes and so that if you feel unsafe or like an escort to and from your classes,” Tackett says. “So when I really started asking for stuff, the guy that assaulted me started following me to and from classes, was yelling stuff at me across campus. And he would say stuff like ‘Oh I hate that bitch over there.’ It’s just really unsettling stuff.”

Tackett finally left the school only two days into the spring 2016 semester after she alleges in her lawsuit that Goldenberg and friends of his on the football team continuously harassed her.

Like Tackett, McClure also had family members who rowed and was looking to make her mark in the sport. Her older sister rowed at the University of Oklahoma.

According to McClure‘s lawsuit, she met her attacker through mutual friends on the football team in August 2015. The attacker, according to Lawrence World Report, was not suspected of using alcohol, drugs or a weapon.

After the alleged assault, she also waited to report it to the authorities.

In October, after a meeting with the rowing team’s sports psychologist, McClure decided to report the sexual assault to the KU Office of Public Safety and the Lawrence Police Department, the lawsuit said.

The Office of Public Safety investigated the assault and sent its findings to the Douglas County District Attorney’s Office for possible prosecution.

According to McClure’s lawsuit, she met with team’s sport psychologist, Sherice Sadberry on the same day she reported her assault.

When McClure did receive therapy on campus, she was less than pleased.

“It’s not even close to the counseling that an assault survivor would need,” she said. “It's not close to campus. It’s not on campus. It’s not easily accessible; it’s a creepy building.”

The University of Kansas is vigorously fighting both lawsuits, the university said in a statement, and has denied the women’s claims.

“We are confident the courts will agree that we’ve met our obligations to both Ms. McClure and Ms. Tackett,” the statement said.

The university did not answer SI’s questions about why Goldenberg was allowed to stay on campus from October 2015, when the complaint was filed to the school, to March 2016, when he was expelled from the university. SI found no records of Goldenberg ever being disciplined by anyone in the school’s administration or the football program, until he was expelled from the university.

McClure also reported her assault to the IOA and says she was repeatedly stonewalled when trying to get services she needed to cope with the assault.

McClure went to the school’s administration two months after her alleged assault, and when Tackett found about McClure’s alleged assault, she too began the process of getting justice and her alleged attacker off campus.

But the disappointment of leaving school and pursing her dreams of rowing bothers McClure, and she lays the blame squarely at Kansas, among others.

“I loved every bit of it," McClure says of rowing. "That was my safe place, that was my safe haven to go to. And I could be the loud, fiery person and not be judged for it. I'm loud, I'm scary. I'm intimidating. I get stuff done. I tell people what to do and I make people winners. That's what I do. And that’s what they took away from me.”

The fallout

Tackett’s mother, Amanda, says that Goldenberg’s expulsion from Kansas is not punishment enough. She fears Goldenberg will attack other women. Goldenberg’s lawyer denied that an assault ever took place, and he has not been charged with a crime.

“She is not the same person. I don’t know she ever will be. I want him prosecuted. I want him behind bars,” Amanda Tackett says as her voice reaches a higher octave with every word. “I want Kansas to pay, someway, somehow. They came across like that would treat her like a family member, that she would be safe, and then they completely shut her out. We were lied to repeatedly.”

Tackett’s mother is done with the talk, the rhetoric, and the promises of nothing being done. For nearly two years, she says it has been a struggle for her family and she is trying to understand how this happened at a place like the University of Kansas.

“My daughter’s life has been turned upside down. There is no excuse for what has happened,” Amanda Tackett says. “People have failed my daughter and my family on multiple levels and yet no one has given us a reason why. Why didn’t they help my little girl, why do they continue to deny they don’t have a problem at that school?”

Daisy Tackett currently attends New York University, where she hopes to continue her education in history and international relations. “I am not doing it for the money. This is not for me. Someone needs to be held accountable. Kansas is a public university and this type of stuff is happening across the board. And it’s needs to stop,” she says. She has also been attending outpatient, group therapy and individual therapy.

“I am pissed. I loved Kansas, but it’s ok to be angry,” she says. "It’s ok to demand stuff, especially if you don’t feel safe and are not treated right. Because at the end of the day, the schools need to step up and take care of us. “

McClure is back home under the watchful eye of her parents, who still have hopes that their daughter achieves the dreaming of returning to rowing and becoming a veterinarian.

“We want her to do the things that makes her happy, we want to have that Sarah back. But whether that's school this fall, which is coming up rather quickly, or if it is the semester after that, we don't really know,” Sarah’s father, James McClure, said. "The timing of when she goes back to school is not the priority. We just want her to be well before she goes off again.”

Now 19, McClure says she misses rowing and feels like a lot of people are responsible for her life today.

“Rowing was a part of me, it legitimately was a piece of me. It was a piece of my heart. It was a piece for me and forever will be. When all of that happened, it felt like they took that away from me. That was a huge part of my life for seven years.”

For now, the therapy, the support of her friends and family will have to do, but she issued a pointed warning to anyone, including the University of Kansas, Goldenberg and anyone else who has gotten in her way of pursing justice and her dreams.

“They picked the wrong people to fight with because I have always gone with this saying in my life is that you never give up,” McClure says. “You never end something, you have to be resilient, you have to keep moving forward. You have to keep pushing because you know there are still many females out there that have been shoved under the rug, not cared about and treated worse than dog crap. And that is the reason we are doing this. I am not going away.”