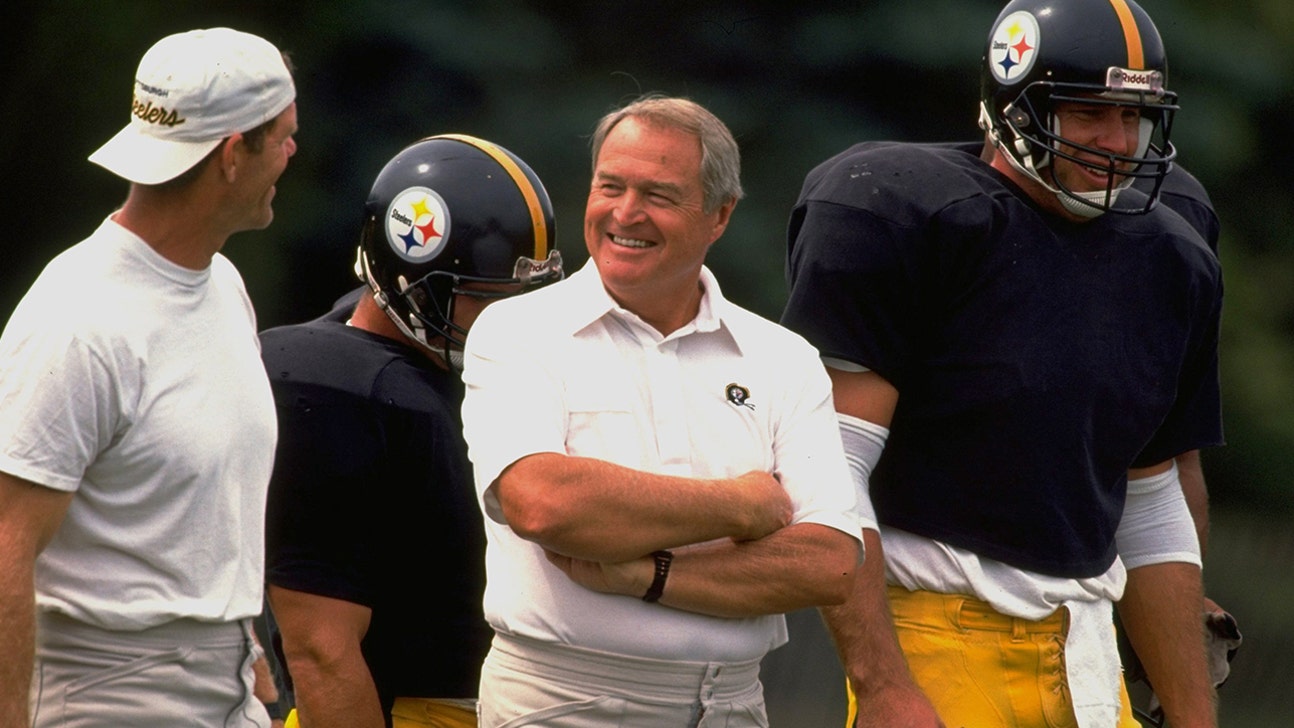

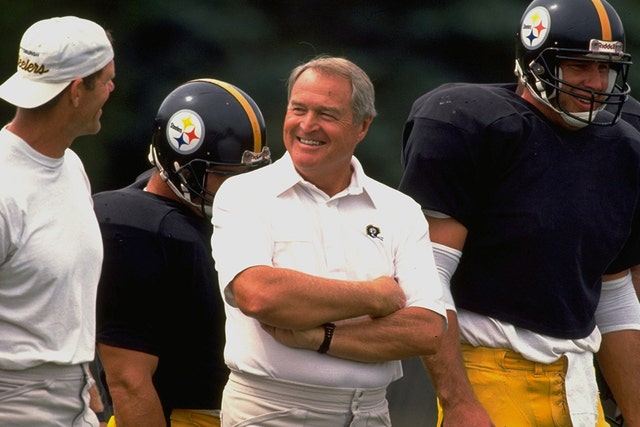

A coach in decline: Chuck Noll's trademark traits faded as Alzheimer's signs worsened

The following is excerpted from CHUCK NOLL: HIS LIFE’S WORK by Michael MacCambridge. Copyright © 2016 by Michael MacCambridge. Used by permission of University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved.

A few weeks after the retirement, Chuck and Marianne were sitting on the Steelers’ private charter jet out of Pittsburgh headed down to Hilton Head. There was one other passenger—Bill Cowher, who’d recently been named to succeed Chuck as head coach. Cowher’s face was an open book: nose broken by too many tackles, thick mustache giving the appearance of a new cop on the beat, an energized conversationalist who occasionally emitted clouds of spittle when he was particularly excited. In personality and demeanor, he was the polar opposite of Chuck.

But Cowher also had a deep respect for football history and the tradition he was inheriting in Pittsburgh. Leaning over before takeoff, he said to Chuck, “I would appreciate your input. Is there anything you think I should know?”

“You’ll be fine,” Chuck said. “Be yourself, do your best, and I am sure you’re going to be fine.”

That was all he offered. Chuck made allowances for neither sentimentality nor mentoring—Dan Rooney had arranged for Chuck to have an office in Three Rivers, but Chuck never went there. He didn’t want to get in the way or have his presence be a distraction.

Of course, Cowher getting the coaching job meant that Joe Greene hadn’t. On the day of Chuck’s retirement press conference, Bill Nunn had brought Greene into his office and counseled him that, while he might be a head coach one day, he was not ready for the job yet. But Greene, as the player most responsible for the Steelers dynasty, and the first—and most important—player Chuck ever drafted, had to be considered for the job.

Chuck Noll: His Life’s Work

by Michael MacCambridge

Within weeks of the retirement announcement, Chuck bought a boot-sized early forerunner to the modern cellular telephones and headed off with Marianne on the boat—“He wanted to be sure he could be reached, so he could help his coaches get jobs,” said Marianne.

Meanwhile, Cowher in his first year coaching the Steelers had to acclimate to what his new team understood to be the norm. “We were practicing once and we were going at it pretty good,” said John Jackson. “Cowher brings the team together and he says, ‘Listen—we’re not playing the Steelers this week! You guys are hitting way too hard.’ Somebody stood up and goes, ‘Coach, this is how we practice. We don’t know any other way.’ We would go back to practicing and he would stop practice again. He’d say, ‘Stop. Take off all your equipment and just leave your helmet on.’ You could hear us hitting. We had to hit somebody. He finally understood, I think, later. But when you raise somebody a certain way, that’s how they’re raised.”

Chuck and Marianne reveled in their freedom, traveling up and down the intercostal waterway, scouting out possible locations before deciding to stay on Hilton Head (they soon sold the house on Warwick Drive, down-sizing and making a clean break from the Steelers’ years).

There was always someplace to go, always something to see. There was good wine, unlimited seafood, and the never-ending conversation of soul mates. “We lived on the boat for months and I loved it,” said Marianne. “I would have stayed there forever.” They journeyed, they fished, they came ashore for a while and explored, then returned to the sea, freshly stocked with wine and provisions, and set out again.

“That was the big joke,” said Chris Noll. “When I was in college, they could never find me. And when they retired, I could never find them. Turn the tables.”

Later in the spring of ’92, Joanne and Glenn flew down to spend time on the boat. They went out to deep water, but as soon as they couldn’t see land, Joanne got seasick. It wasn’t until they went back to the intercostal waterway that her stomach calmed. It meant that their route down the coast was less direct, and that there was more traffic.

“That was my first encounter with Chuck’s intensity,” said Glenn Mikut. “So we are coming upon this one drawbridge and they show the height of the water, he knows the height of the boat and everybody is waiting for the drawbridge to go up, which is every half hour or whatever it is or whenever they have enough boats to go under, right? So Chuck decides through this calculation that we can make it. So he starts going. Everybody else is staying back. There’s Chuck, full speed ahead. And Marianne and I are up on the top. The mast is up there. We are like eyeing it, and Chuck is screaming, “Are we gonna make it or not!?” All of these expletives and everything. And I’m like, “I think we can make it,” which is not good enough with Chuck. There is no gray area there. It’s like, ‘Yeah!’ You are better off saying yes and breaking the mast off because then you have made a decision. We made it. Thank God. I’m still here. I would have been fish bait.”

People who know football coaches often can’t imagine them doing anything else. So there had been murmurs, and others thinking that he might one day consider a return. But a year into his retirement, Jack Henry—Chuck’s last offensive line coach—phoned the house on Warwick Drive. The Giants had just fired head coach Ray Handley, and general manager George Young (who’d worked with Chuck in Baltimore) was looking for a veteran coach.

Henry was getting ready to take an assistant’s job with Pitt, but he first wanted to see if his old boss might consider returning. But Chuck had never wavered.

“No, it’s over for me,” he said. “I’m done.”

Another call came, two weeks later, informing Chuck that he’d been elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. There were many letters of congratulations in the weeks to follow, perhaps the most eloquent written by Artie Rooney, who’d mellowed in the nearly seven years since his brother had pushed him out of the personnel spot.

“You more than anyone I know deserve this honor,” Artie wrote to Chuck. “You were like Moses leading us through the Red Sea and across the desert to the ‘Promised Land.’”

That spring, on an annual golf outing at a resort in Tennessee, Chuck casually invited many of his Dayton friends to come to the late summer induction ceremony.

Later that summer, they all converged on Canton—sixty miles south of Cleveland on Interstate 77—for the induction ceremonies, while thousands of Steelers fans made the two-hour drive to be there for the enshrinement.

On the embankment near the front entrance of the Hall of Fame, the cramped amphitheater where the ceremonies were held, the Pittsburgh faithful did something they’d never done during twenty-three seasons at Three Rivers. They began a chant just for the coach. “We Want Chuck! We Want Chuck!” they thundered, and all he could do was bashfully smile.

Chuck’s speech was filled with platitudes, but it was also heartfelt. As he strode to the podium, he said, “[fellow inductee] Dan Fouts is holding the money for the guy who cries the longest . . . and I’m gonna win it.”

But he remained composed throughout the ten-minute speech, which emphasized the importance of teamwork and decried the way—in his view—modern society seemed to naturally embrace conflict (“male vs. female, black vs. white, labor vs. management”).

“Right now, you hear about teamwork,” he said, “and it’s defined as 50–50, and that is a falsehood. There’s no such thing as 50–50. You know, you do whatever you have to do as part of the team.”

There were two things about the speech that only seemed noteworthy many years later. In citing the example of teamwork, he mentioned the day against the Oilers when the offensive line was decimated by flu and the quarterback was injured, and he described the defense rising to the occasion—“Joe Greene was in the running lane, and Jack Lambert was hammering on them.” Later, Chuck mentioned the first game at Three Rivers, as a preseason game in 1970 against the Jets—“That was the team we lost to in Super Bowl III.” And only someone who was intimately familiar with the history of the franchise, or was being scrupulously literal, would have quibbled with Chuck by pointing out that the game he mentioned against the Oilers was played in 1972—two seasons before Lambert arrived in Pittsburgh—and that the preseason game was actually against the New York Giants, not the New York Jets. They seemed small oversights at the time, simple lapses in memory. Only later would people look back and wonder, Was it a sign?

That entire day, there was a crush of friends and family. The Dayton teammates had been reveling in their friend’s great moment, drinking and celebrating. Jim Reiff, wheeling Jerry Von Mohr around, came up on a hill and the legless Von Mohr slipped out of his wheelchair. “What’s the matter with you!?,” protested Reiff. “Can’t you even hold on?” Somewhere, Marianne rolled her eyes.

After the ceremony, there was a party back at a local hotel. But even in his moment of glory, he was mindful of family commitments. Chuck waited for his cousin, Pete Schreiber, and Schreiber’s daughter, to get back from a softball championship game she had to play that day in Cleveland.

“I’m not leaving until Pete comes with his daughter,” Chuck said.

In 1995, the Steelers returned to the Super Bowl for the first time in fifteen seasons. Chuck wanted to be there; some of his old players— Rod Woodson, Dermontti Dawson, Carnell Lake, Greg Lloyd, Neil O’Donnell—formed the nucleus of the team that Cowher had built into a perennial contender.

That week in Phoenix, Chuck did a series of commentary pieces for KDKA in the week leading up to the game, mostly remembrances of his experiences in the previous Super Bowls.

Just as Chuck had so often done, Cowher got the Steelers to play their best game—hanging with a superior Dallas team for much of the game, before Neil O’Donnell made an ill-timed pass, intercepted by the Cowboys’ Larry Brown and returned for a touchdown. The Cowboys won, 27–17.

After the game, Chuck and Marianne drove to the Doubletree Hotel in Paradise Valley for the postgame party, a muted affair in which the Steelers’ administrators and players were gathered. As they were walking toward the front door of the banquet hall, Chuck stopped.

“I don’t want to do this,” he said to Marianne. And they turned around and left.

“It broke his heart when they lost,” said Marianne. “Those were his guys.”

It was January 1999, less than a week after Chuck’s sixty-seventh birthday, when he traveled to Orlando with many of his old coaches—George Perles came, as did Woody Widenhofer, Rollie Dotsch, and Joe Walton.

Chuck had been invited to coach one of the teams in something called the First All-Star Gridiron Classic, which matched a team of college seniors who’d played high school or college ball in Florida against Team USA, of players from around the country.

On Thursday, January 14, two days before the game, he was instructing one of his players in a backpedal technique when he collapsed to the ground. His Achilles tendon—the same one that had troubled him on and off since at least his days at Dayton—finally snapped. When Marianne returned from her outing that day, she found Chuck in a full leg cast in the hotel. They left before the game—“I certainly wasn’t going to spend two months in Disney World,” she said—and Joe Walton took over Team USA.

It seemed like a blip at the time, but the recovery from the injury took nine months. Convalescing from his torn Achilles, Chuck took longer than expected to get back to his old self. Moving around awkwardly with a scooter, gaining weight, he seemed unusually sluggish and struggled to regain his old mastery.

“They were kind of living the life on the boat, and having a blast doing that, and he was doing some stuff with the NFL,” said Chris. “But then it kind of started with the torn Achilles, and from then on it was just one thing after another.”

Looking back, all those closest to Chuck agreed that his larger health troubles began with the injury and lengthy recovery. “It was the anesthesia that started to accelerate stuff,” said Chris.

One night, a few months later, Marianne and Chuck were having a quiet night at home. They’d turned in and were in bed, her head resting on Chuck’s chest, when she realized something was amiss.

His heartbeat was irregular. They went in to have it looked at the next day and discovered a defective heart valve, which they hoped could be managed with medication. By then, they both agreed than another operation was out of the question.

Throughout the years of Chuck’s retirement, the issue that kept coming up repeatedly was Terry Bradshaw. Virtually every other Steeler of significance seemed to have reconciled his relationship with Chuck. Bradshaw had written two autobiographies—Looking Deep (1989) and It’s Only A Game (2001)—the unifying theme of both being his own searing insecurity, bracing self-disclosure, and the degree to which he still felt done wrong by Chuck—even as he reluctantly acknowledged that Chuck was vital to his development. “I played for a coach, Chuck Noll, whom I never understood and who never really understood me; I loved him but we parted badly, and haven’t really spoken since,” he wrote in the preface to It’s Only A Game.

Later in the book, Bradshaw wrote, “I’d like to be able to say Coach Noll helped me. I really would like to be able to make that claim—but it wouldn’t be true. Chuck Noll took to me like a duck takes to an oil spill. . . the scars he inflicted on me those first few seasons never went away.” For his part, Chuck never rose to the bait, and so the cold war was largely one-sided.

At the 2002 Daytona 500, Cliff Stoudt was there as a guest of the driver Michael Waltrip, and on pit row, he ran into Bradshaw, who’d had a team that raced in a preliminary event on Saturday.

The publication of It’s Only A Game had brought Bradshaw’s complaints back to light.

“When are you going to give it up, Terry?” Stoudt asked. “I mean, damn—the man treated you exactly how you needed to be treated, and that is why you did everything you did. He never was harder on you than anybody else. He gave you the reins to go ad lib with whatever you wanted to do, and he sat on you when he needed to.”

Bradshaw still carried a grievance over Chuck speculating that it might be time to get on with his life’s work and mentioned that to Stoudt.

“Terry, that wasn’t a slam at you—that was protecting me,” Stoudt said. “I had to go out there and replace you after winning four Super Bowls. Chuck was just trying to say, ‘Let’s not bring up Terry Bradshaw every day.’”

Bradshaw conceded the point, but still felt aggrieved. In 2003, Bradshaw was slated to be the guest of honor at the Dapper Dan Dinner in Pittsburgh. In an attempt at reconciliation, Bradshaw asked the event organizers if Chuck would be willing to introduce him. When asked, Chuck readily accepted. The day of the event, February 9, 2003, the Post-Gazette’s Ed Bouchette wrote a story about the significance of the reconciliation. The headline told much of the story: “One-Way Feud Finally Ends as Bradshaw Shows Appreciation, Love for Noll.”

The men’s contrasting personalities—when uncomfortable, Bradshaw was all emotion, and Chuck was all intellect—made it unlikely that they would find an easy sense of closure. Chuck remained cordial throughout the evening’s dinner. Bradshaw was polite and deferential behind the scenes that evening, then gushed once he got up on the podium.

Alternately abashed and tearful during his talk to the banquet, Bradshaw apologized “for every unkind word and thought I ever had,” and claimed that he and Chuck were now close. “If we lived in San Francisco, we’d be married now,” he said, the tasteless joke falling mostly flat. A year later, when Bradshaw was roasted at the Mel Blount Youth Home annual dinner, he told Chuck they’d play golf. But he never called.

For other players, who didn’t have the issues Bradshaw had, it was still odd—even surreal—to see their old coach. Later in 2004, at a card show, Chuck saw Gary Dunn—whom he hadn’t spoken to since Dunn’s playing career ended in 1987. It was an event at the Pittsburgh Convention Center. “It was kind of weird because everybody is getting paid to be there, and Chuck is right next to me signing autographs,” said Dunn. “And Chuck is being paid to be there; I know he is not doing it for nothing. And it was just a weird, different thing, because now he is not my boss, and we just talked. And you know, we talked about things back then. And we laughed. He couldn’t be nicer. A different guy, totally different. There was so much to him. When I had him in that situation, I couldn’t believe it was Chuck just talking on. But see, I wasn’t as scared either. I was saying whatever I wanted. It was very good.”

At the same show, Ron Johnson walked over and asked Chuck to sign an autograph for a client of his. “Ron, if it will help you make a sale, I’ll sign it.”

John Stallworth also visited with Chuck at the same event. “He asked a little about my business,” said Stallworth, “and we were doing well, and he had heard about how well we were doing in the business. He asked me about that and that probably was the longest conversation I had with him. I don’t know that I was ever totally at ease talking to him, and so in that sense, the brief conversations were okay.”

On his good days, even those who loved him couldn’t tell much of a difference in Chuck’s demeanor. But there were more off days, each of which provided glimpses that something wasn’t right.

The litany of health setbacks diminished him and made traveling more of an effort. When his older brother, Bob, died in the summer of 2002, some relatives noticed that Chuck seemed different at the funeral, more distant than usual, slower to recognize them. Pat Manning died of cancer the same year, and though Chuck and Marianne attended the funeral, he was clearly laboring, his extended health troubles leaving him visibly weakened.

In Pittsburgh, they began spending even more time with Glenn and Joanne, and Chuck would often show Glenn his latest photography. “So we would go on the computer and we’d go through the pictures,” said Glenn, “but we kept going through the pictures more than once, and he wasn’t sure if he looked at them yet. So I thought that it was just him getting old and just forgetful.”

Marianne had noticed a loss in sharpness ever since the torn Achilles.

After going under for the surgery, Chuck seemed less mentally nimble for a long time afterward. And now she wondered, Had he ever fully recovered? Is this him? Or is this the new normal?

No one wanted to say it, but they couldn’t help but notice. The man with the formidable intellect and voracious thirst for knowledge had slowed, he seemed less sharp, less focused, less mentally acquisitive.

On April 24, 2004, the family gathered in Cleveland for Jerry Deininger’s wedding to his girlfriend, Maria. The youngest boy of the seven siblings, and the last to marry, Jerry had missed out on some of the time that the others had enjoyed.

It was a festive weekend, with Rita surrounded by her brood, and Chuck and Marianne in for the weekend. That was the weekend that the nieces and nephews first sensed something was wrong.

“He walked into the room, and as soon as I saw him, I went up and hugged him,” said Margie, “and he was real stiff and cold. I didn’t know how to interpret that.”

Nothing was said to Chuck and Marianne. Joanne fretted to herself and later to Glenn.

“Forever, the two of them worked so well together,” she said. “He couldn’t think of a name, and my aunt would tell him.”

That summer, with the extended family at the vacation home in Williamsburg, Chuck kept losing his way back from a restaurant, prompting Chris to lose his patience.

“I was getting angry and getting angry, and then finally I realized something was wrong,” said Chris. “I wasn’t around him that often. So we would be on vacation, and we were together for two weeks, and it was really clear because he covers it so well.”

He continued to do so, often quite successfully. That same year, Chris, Linda, Katie, and Connor came down for Thanksgiving, to see the new condo Chuck and Marianne bought, on the main street in Sewickley. The four-year-old Connor was sporting a form-fitting Spiderman costume and mask that day. Chuck walked through the supermarket in Sewickley, holding hands with his tiny Spiderman. On Thanksgiving day, Chuck and Chris tried to smoke the Thanksgiving turkey and wound up setting off the fire alarm, bringing a fire truck (to Connor’s delight) to the condo. It was, if one didn’t look too closely, a typical Noll holiday gathering.

But for all of them—Marianne, Chris and Linda, Glenn and Joanne—a nameless disquiet hung in the air. The heart troubles worsened, as did the bulging disc in Chuck’s back. A visit to the hospital only exacerbated things, leaving Chuck with a staph infection and in critical condition in an intensive care unit. The recovery time for each malady was slower than usual. On the streets of Sewickley, late in the summer of 2005, when Marianne saw the Steelers’ Dr. Joe Maroon, he asked about Chuck’s back.

“We have the X-rays at home,” Marianne said.

“Well, let me stop by and take a look at them,” said Maroon.

“Sure,” Marianne said, then paused, before continuing. “But we’re dealing with something else now. It’s worse than the damn back . . .”

The connection between boxers and dementia was a clear and understood reality for decades in American sports. The connection between football players and Alzheimer’s was more tenuous but no less a factor. The results of the landmark study of 3,439 ex-professional football players—which revealed that players were four times more likely to suffer ALS and Alzheimer’s disease as the general public—were not yet conclusive.

Chuck had heard in 2001 about his old teammate Otto Graham, who’d been diagnosed with early stage Alzheimer’s. Across pro football, the disease took root. The vacant eyes, the repeated anecdotes, the slurred speech. He’d begun to see some of those traits in his own players.

At Maroon’s behest, Marianne took Chuck for a battery of tests, during which he maintained an imperturbable good cheer. “Here, hold my watch and ring,” he said to her before the MRI.

After the tests were completed, they went to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center to see Dr. Steven DeKosky, the head of neurology. The CT scan results were clear enough—there was damage. DeKosky showed them both the pictures, then asked Chuck to step outside for a moment.

After Chuck stepped into the hallway, DeKosky leveled with Marianne, uttering the inevitable, dreaded word.

“He has it,” DeKosky said. “He has Alzheimer’s.” Marianne listened numbly, as he continued.

“Now you have to call your family,” DeKosky said. “Call the people you think it is important to know this. Call your attorney. And Marianne —you have to tell Chuck.”

A few moments later, she left. Chuck and Marianne drove back to Sewickley mostly in silence, NPR playing over the car stereo. They parked and headed up the stairs. She had Chuck sit in his favorite chair, in the corner of the living room, close to the window, where he could see out to the patio and the street, just across from the television set that was off.

“Okay, we have to talk,” she said.

She went to the kitchen and collected herself and then returned and sat down opposite Chuck on the footstool.

She took his hands in hers and delivered the news: “The doctor says you have Alzheimer’s disease.”

Chuck looked back at her. There was a long moment of silence. And she could see him weighing the reality, and the implications, and a life-time of things that had been left unsaid.

Then he squeezed her hands tightly and looked back into Marianne’s eyes, with the steady, determined gaze she’s seen so many times before. He had just one thing he had to tell her.

“I will . . . never . . . forget who you are,” he said. Then they embraced and dissolved into tears.