Pro Football 101: Paul Warfield ranks No. 47 on all-time list

By Joe Posnanski

Special to FOX Sports

Editor's Note: Throughout 2021 and 2022, Joe Posnanski is ranking the 101 best players in pro football history, in collaboration with FOX Sports. Posnanski will publish a detailed look at all 101 players on Substack. The countdown continues today with player No. 47, Paul Warfield.

One of the funny and wonderful things about sports is that all of us, no matter who we are, begin watching with the show already in progress. There’s a whole history of sports that happened before we were born, before we became aware, and we just sort of catch up the best that we can.

That is to say we aren’t born knowing who Henry Aaron is, who Joe Montana is, even who Michael Jordan is. We learn. Maybe a parent points one out with unusual reverence. "Son," Bob Costas remembers his dad saying the first time they went to the Polo Grounds together. "See him. No, the one in the middle. That’s Willie Mays."

Maybe we see a photograph that grabs our attention. Who’s the boxer standing triumphantly over that crumpled figured on the mat? Who’s that hockey player flying like Superman in front of the net? Who’s that tennis player being carried like Cleopatra to play in a match against a man?

Maybe we catch a highlight of a blurry, black-and-white Babe Ruth running pigeon-toed around the bases. Maybe we read a story about Joe Namath toddling around the New York scene. Maybe we overhear a conversation about how these kids could never stand up against Wilt Chamberlain.

Somehow, gradually, step by step, we begin to piece together a larger picture of the sports world.

In 1976, when I was 9 years old, the Cleveland Browns re-signed Paul Warfield. He was 34 years old by then, and I had absolutely no idea who he was. I was at that embryonic stage of sports fanhood when I knew only the basic rules, when I knew only the names of a handful of players, when I was still trying to catch up on the basics. But I could sense, from the hushed tones of the adults who talked about it — our neighbors, the school bus driver, the teachers at school — that this was someone different, that Paul Warfield was something special.

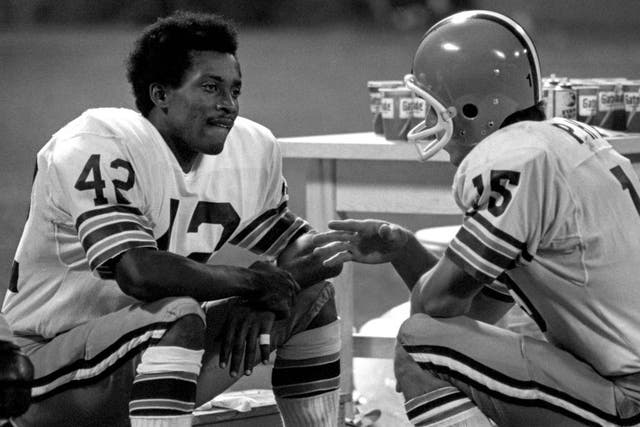

In two stints with the Cleveland Browns, Paul Warfield caught 271 passes for 5,210 yards and 52 touchdowns over eight seasons. (Photo by Ron Kuntz Collection/Diamond Images via Getty Images)

Looking back, it can be difficult to find that specialness in the statistics — in one of his All-Pro seasons, Warfield caught just 29 passes, which is basically two games for Cooper Kupp — but it’s important to remember that wide receivers filled a different role in the 1960s and 1970s. Warfield was a nuclear bomb, one used more as a deterrent than as a weapon.

That All-Pro year when he caught just 29 passes — that was 1973 for the Super Bowl champion Dolphins — Warfield scored 11 touchdowns. That was an extreme version of his entire career; 20% of his catches were for touchdowns. One out of every five.

But that’s all he could be in his time. Warfield played for two of the most conservative offenses in NFL history — the Jim Brown Browns and the Don Shula Dolphins — and played in a time when defensive backs could essentially tackle, assault, pummel and maul receivers to their hearts’ content. We can only imagine what kind of numbers Warfield would put up in today’s wide-open game.

In his own time, he served as a constant warning to defenses: Pay attention, or I will score a touchdown on the very next play.

With the Dolphins in the early 1970s, Warfield was a constant deep threat and converted one of every five catches into a touchdown. (Photo by Focus on Sport/Getty Images)

Warfield was a breathtaking athlete. He grew up in Warren, Ohio, about 60 miles east of Cleveland, and in high school, he was a football and basketball star. He was so gifted that even though he wasn’t especially interested in baseball, several major-league clubs tried to sign him. But it was track where he made his mark; he set state records in both the broad jump and the 180-yard hurdles.* He might have been an Olympian if that had been his path.

*I don’t get the 180-yard hurdles distance, either.

Instead, he chose Ohio State for football, where he got a taste of his future by playing for the uber-conservative Woody Hayes. It was probably Hayes who first said, "Three things can happen when you throw the ball, and two of them are bad."* As such, he played Warfield not at wide receiver but instead at halfback and defensive back.

That is … until his last Michigan game.

*The other person often credited with that quote is legendary Texas coach Darrell Royal, but Royal himself claimed Hayes said it first.

You probably don’t need me to tell you how important beating Michigan was to Woody Hayes. He hated Michigan so much that he refused to even say the word; he just called them "that team up North." He famously once ran out of gas in Michigan and said he would push his car over the state line before he’d spend a dime buying gas in the state. And with Warfield starring as a running back, the Buckeyes put up 50 on Michigan in 1961. In 1962, Hayes mostly shelved Warfield and instead kept giving the ball to his bruising fullbacks; Ohio State won 28-0.

Warfield played running back for Woody Hayes' Ohio State Buckeyes for much of his college career. (Photo by Hy Peskin/Getty Images)

Then came 1963 and a surprise Hayes saved just for Michigan: He put Warfield at wide receiver for the first time. Then, absurdly, Ohio State kept trying to throw bombs to him.

"We’ve always been a good passing team," Hayes said afterward with a big smile on his face. Hayes was never known exactly as an innovator or an X's and O's type of coach — he coached football the way his hero George Patton waged war — but he took enormous pride in recognizing what an extraordinary threat Warfield could be as a receiver. In the game, Warfield caught five passes for 76 yards and the game-winning touchdown; he also had a touchdown catch overruled when the ball bounced out of his hands after he hit the ground.

Hayes was so outraged by the call that he raced all the way to the end zone to scream at the officials. Ah, that Woody Hayes.

*** *** ***

There is probably something worth saying about Paul Warfield and Gale Sayers. They were almost the exact same size (at 6-foot, 198 pounds, Sayers was a few pounds heavier), both high school track stars, both electrifying talents, and they were born just six months apart. Warfield was a first-round pick of the Browns in 1964. Sayers was a first-round pick of the Chicago Bears in 1965.

And there was some question about which position each should play.

The Bears, to Sayers’ great relief, kept him at halfback. He did not want to be a flanker, didn’t believe he could make enough of an impact on the game out there.

The Browns did not have the same option. They already had a pretty decent running back named Jim Brown. So they put Warfield at wide receiver (after considering him as a defensive back).

Those decisions altered professional football in the 1960s and into the 1970s. Sayers was a flash across the sky. He became, I believe, the most beautiful runner in the history of pro football, but the concerns that he was too slight to endure the pounding proved to be true. He played all 14 games in a season only once and was essentially finished at age 27.

Warfield, meanwhile, had a long NFL career — 13 seasons — but spent so much of it drifting into the background as a decoy. In his rookie season, he caught 52 passes for the Browns and was an important part of Cleveland's NFL championship. He would never again catch that many passes in a season. He would never be the focal point of a team’s offense.

So he made the most of what he had. Probably the closest he ever came to being the team’s No. 1 option was in 1968 for the Browns — he caught 50 balls for more than 1,000 yards and an NFL-leading 12 touchdown receptions. But that was still a run-first team (with Leroy Kelly replacing Jim Brown as the star), and the Browns started to think that Warfield was not enough to win with. They needed a quarterback.

A year later, they traded Warfield to the Dolphins for the No. 3 pick in the draft — a pick that turned into quarterback Mike Phipps.

In 1976, upon his return to Cleveland, Warfield played with QB Mike Phipps, right, who was drafted with the pick the Browns acquired for trading the receiver to Miami six years earlier. (Photo by Ron Kuntz Collection/Diamond Images via Getty Images)

It is probably the worst trade in the history of the Cleveland Browns franchise.*

*There’s a great story about that. The night of the trade in late January 1970, Browns coach Blanton Collier was at something called the "Ribs and Roast Dinner," which was held annually to promote Cleveland baseball. Before the dinner could even get going, a red-faced Youngstown sports editor named Larry Stolle rushed over to Collier and started screaming, "You did what? You traded PAUL WARFIELD?"

Collier hemmed and hawed, called Warfield the finest receiver in the NFL, but insisted the Browns just had to get a quarterback.

"You tell me," Collier said, "what happens if [quarterback] Bill Nelson gets hurt early in the season? Who runs the ballclub?"

"You tell me," Stolle fired back. "Where are you going find another end like Paul Warfield?"

*** *** ***

Dolphins coach Don Shula sensed that Warfield was exactly what his team needed. And Shula was right. Miami was 3-10-1 the year before Warfield arrived. The next five years, the Dolphins made the playoffs every year, played in three Super Bowls, won two of them and had an undefeated season.

"He was the player who gave our team balance," Shula said. The Dolphins were certainly not a balanced offense — they ran the ball about two-thirds of the time — but all the while, defenses had to plan for Warfield. They had to think about him constantly.

It’s really funny — from 1971 through 1973, the Dolphins made the Super Bowl each year. In that time, Paul Warfield was the most dangerous receiver in professional football. And in 23 of those 42 regular-season games, Warfield caught two or fewer passes.

It was just his destiny.

Warfield played a year in the World Football League in 1975 and then, as mentioned, came back to the Browns in 1976. He was 34 years old but still had enough of the old greatness to lead Cleveland to a winning record after a couple of disastrous seasons. I remember thinking there was just this coolness about him. Everything he did on the field had just a little more style.

Joe Posnanski is a New York Times bestselling author and has been named the best sportswriter in America by five different organizations. His latest book, "The Baseball 100," came out last September.