How fans — or the lack of them — can impact performance at the Tokyo Olympics

By Cassidy Krug

Special to FOX Sports

The stands are largely empty in Tokyo. How does the lack of an audience change the game for elite Olympic athletes? It depends on the athlete.

My first international diving meet was in 2004 in Zhuhai, China. I was 19. I remember standing at the bottom of the ladder, shivering with excess nerves, praying my legs would somehow stop shaking when I got to the top.

At home, I was used to sparse audiences full of Gameboy-playing siblings and bored aunts and uncles. But diving is practically China’s national sport, and in Zhuhai, the stands were full, floor to rafters. Smoking was allowed inside, and when I looked up, the top of the natatorium was enveloped in haze.

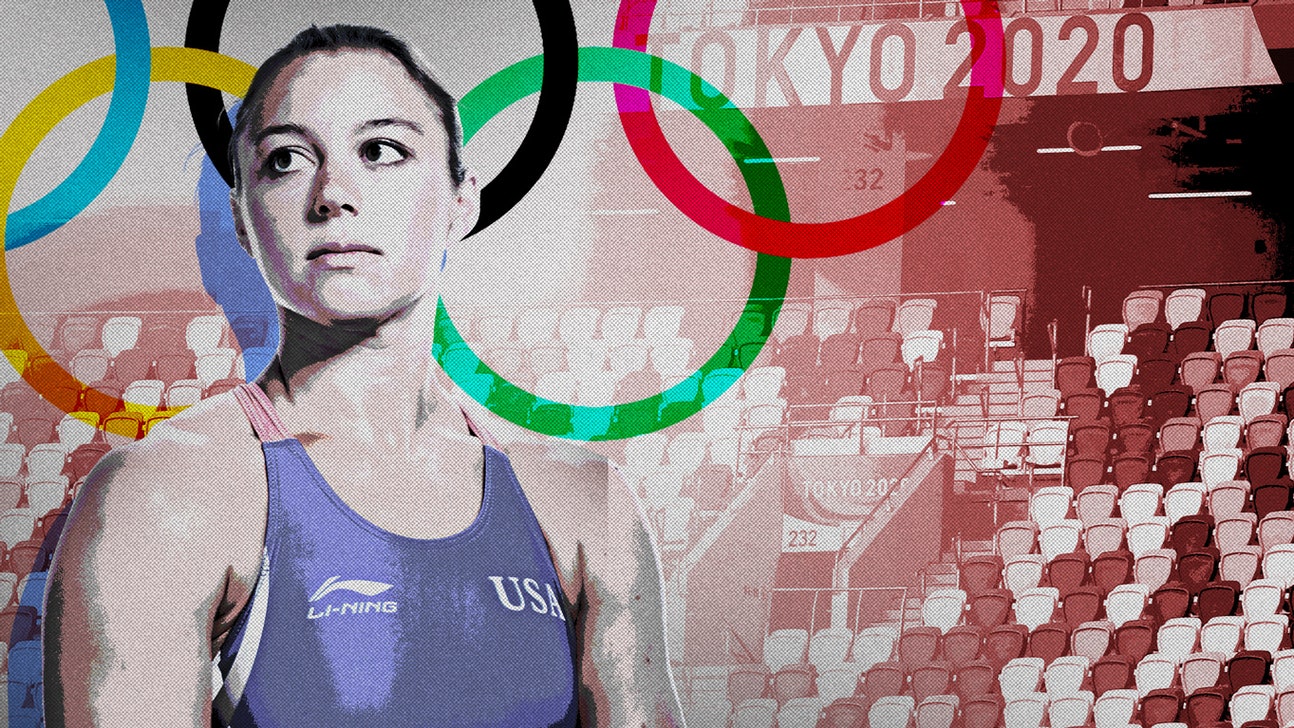

During her career as a competitive diver, Cassidy Krug performed in front of a range of audiences — from dozens of fans to many thousands. (David Eulitt/Kansas City Star/Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

The diver before me hit the water and I started climbing. With each rung my anxiety rose. I got to the top and my name and my upcoming dive, a front three-and-one-half pike, were announced. The garbled, deeply accented voice triggered an urgent desire to be back on the ground, holding the poles of the ladder, waiting my turn.

I wished it was five minutes ago, when I was hopping around on the ground to warm up, or yesterday, when I was watching Chinese sitcoms in my hotel room and eating Nutella out of a jar.

I wished it was any time but now.

The announcer finished, giving way to the sounds of shuffles and shoe squeaks from the stands. I stood for a few extra seconds, taking the deep breaths the sports psychologists recommended. My lungs quivered through what was supposed to be a calm, measured intake, drawing in oxygen in fits and starts.

My goal in meets was to focus on two cues and let my body do the rest. In this moment, I was supposed to be thinking, "Hold your arms up on the hurdle jump," and, "Keep your head in on the come out." But it was taking all my mental energy to keep from collapsing.

I started my approach. My legs moved like they needed to be oiled. After four steps came the hurdle jump — a dynamic maneuver meant to land me perfectly on the end of a moving diving board. I did not hold my arms up.

Instead, a mistimed muscle flex sent me in the wrong direction, and I Ianded with eight toes hanging over the front end of the board and the other two hanging off the left side.

The dive was supposed to be three-and-one-half somersaults. It didn’t make it past three-and-a-quarter. I crashed into the pool, sending up a bomb of water. When I emerged, waves were hitting the deck and thousands of people were forcing guffaws out of their chests.

I later learned that in Zhuhai, the appropriate way to respond to athletic misfortune is to laugh, loud and long.

The medal ceremony for the men's synchronized 3m springboard diving competition took place in a mostly empty Tokyo Aquatics Centre last week. (Photo by OLI SCARFF/AFP via Getty Images)

It's Different This Year

A live audience can be a force of pure power, one with the potential to elevate some athletes and destroy others.

This force is largely missing from the Tokyo Olympics this summer. Cavernous arenas echo when announcers speak. Gold-medal performances are met with applause so sparse you can hear the individual claps. Olympic organizers are dulling the silence by piping in crowd noises, but suffice it to say — it’s different this year.

For more up-to-date news on all things Summer Olympics, click here to register for alerts on the FOX Sports app!

I competed internationally for the U.S. for eight years, culminating in a berth on the 2012 Olympic diving team. Throughout my career, I asked one question frequently: Why does performing in front of a crowd — and on a larger scale, the pomp and pressure of huge competitions like the Olympics — cause some athletes to fight, and some to freeze?

Here’s what I learned working with some of the best sports psychologists in the biz.

Big competitions, big crowds, and big moments increase arousal. This feeling of boosted muscle tension and narrowed focus has a lot of names in sports — jitters, nerves, adrenaline, juice. You can picture the relationship between arousal and performance as a dome shape. Too little and athletes are lethargic; too much and they choke. The top of the dome is the sweet spot, where strength and focus reach their zenith.

At the 1976 Olympics, Caitlyn (then-Bruce) Jenner broke the decathlon world record with eight personal bests — that’s eight personal bests in 10 events — and talked about having "a feeling of awesome power, of rising above myself, doing things I had no right to be doing."

The stands were almost completely empty for this men's beach volleyball match between the USA and Switzerland last week. (Photo by Yuri CORTEZ / AFP) (Photo by YURI CORTEZ/AFP via Getty Images)

At the top of the dome, the pressure of the Olympics makes diamonds, spurring athletes to perform beyond what they thought possible for themselves.

Not all athletes have the same shaped dome. Runners, cyclists and swimmers tend to race a lot faster than they train. But in an ultra-complex sport like diving, your success relies upon the ability to perfectly time a bending springboard and kick out of a dive at exactly the right height above the water. Extra muscle strength can easily set the whole system out of whack.

When your competitions last hours, not seconds, and require up to 30 minutes of sitting between each dive, hyper-focusing on the wrong things — the draftiness in the natatorium, the possibility of failure, or your unreliably jumpy muscles — can lead to disasters of Zhuhai proportions.

This is one reason why sports like diving are so quiet, relative to say, the raucous stadiums of track and field, basketball and soccer. Diving is complicated. A noise, a yell, a momentary flash of a camera, can all have a serious impact on the fine-motor movements required of divers.

We’re not alone in this. Golf is famously hushed; even the commentators whisper. Archers draw their bows and shooters steady their hands in silence. Does that make the lack of crowds irrelevant for these athletes?

Close your eyes and imagine the sounds of 17,000 people trying to be quiet and then tell me.

Normally competing in front of huge crowds, track and field athletes in Tokyo are performing this week in front of very few fans. (Photo by David Ramos/Getty Images)

Even within a single sport, there’s variation in the curve. About half the divers I competed with relished competition; the bigger the stage, the better they performed. When I asked 1992 Olympic silver medalist Scott Donie recently what he missed most about diving, he said it was that competition high.

"I loved getting super nervous, and then having access to this ability," he told me. "The more people watching, the better."

Some people, like Scott, seem to be born with an easy relationship with adrenaline.

In these quiet Tokyo Games, you might expect that athletes like me — those with a tendency toward overarousal — to thrive, while athletes like Scott might suffer. And it might be just a little bit true.

But keep in mind, athletes aren’t robots, destined to perform according to the physical and mental traits they were born with and the environments they’re dropped into. They have the power to overcome internal and external forces to compete as the best versions of themselves.

For me, that meant overcoming my stage fright. There was the physical work. The more you practice a sport like diving, the more likely it is that you’ll be able to channel and control the epic forces of crowds, competitors, and that once-in-a-lifetime feeling.

There was also the mental work. I visualized diving in front of thousands of screaming, cheering, or jeering fans. I learned to reinterpret jittery muscles as "strength" and terror as "excitement." I learned to spend my time between dives listening to music that worked for me — not 170 beats-per-minute hype tracks, but something slower and steadier to calm my racing heart (shoutout to AWOLNATION — "Sail" got me through my Games).

Ultimately, it worked. The best competition in my life was also the biggest: the 2012 London Olympics. I registered the glitter of bright lights on water, and the crowds packed floor to ceiling — 100 times, maybe 1,000 times more people than Zhuhai, in stands that went up so high I couldn’t see to the top.

I stood calmly at my starting place, living fully in the fullest moment of my life, and I was not afraid.

Krug placed seventh in the women's 3m springboard diving competition at the 2012 London Games, the best finish by an American. (Photo by Clive Rose/Getty Images)

For athletes this year, "doing the work" means making their own energy without the power surge of a buzzing arena. This year, instead of imagining full stands, athletes have been closing their eyes at night and visualizing their best races, routines and dives in front of empty ones.

As they prepare, they’re choosing music that pumps them up, rather than slows them down. Some, like street skateboarding bronze medalist Jagger Eaton, are taking control by keeping their headphones in while they compete. Athletes in "wait-your-turn" sports like diving might watch the leaderboard more closely to increase the urgency.

The most glorious thing to witness has been athletes and coaches taking the vibe into their own hands, cheering and celebrating each other louder and prouder than ever — in some cases, with aggressive hip thrusts.

The fan ban has turned the role of audience member at the Olympics from recreation to responsibility, and judging from the cacophony of whistles, chants, shouts, and — is that a vuvuzela? — at the swimming venue, they’re taking that responsibility seriously.

Will athletes be able to reach their peak at the Tokyo Games? As always, some will, some won’t. In a press conference following her stunning withdrawal from the gymnastics team event, Simone Biles noted that not having an audience contributed to her stress in Tokyo.

Many gold-medal-winning swimming times this year have been slower than they were in Rio in 2016, an unusual stall in a sport where the bar is expected to rise every four years.

But across sports and venues, athletes continue to go about the business of bringing the best out of themselves. In spite of empty stadiums, Japanese athletes are still feeling the home-field advantage — Japan, which ranked sixth in the 2016 Olympic medal count, is currently tied for fifth at these Games.

Gold-medal times in the pool are slower than expected, perhaps a result of not having fans to offer encouragement. (Photo by JONATHAN NACKSTRAND/AFP via Getty Images)

British diving superstar Tom Daley, who won gold in the men’s platform synchro event, summed up the impact of an empty natatorium matter-of-factly: "Obviously with 15,000 people, it would have changed the dynamic massively, and that would have been great. But you know, as soon as the whistle goes, it goes silent, and that moment is the same whether there are people there or not."

A crowd is powerful, but it’s not the only thing. The impact of the audience pales in comparison to the impact of the competition itself: the best in the world, experiencing the (for some) once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to compete against the best in the world, at their best, on the stage that matters most.

That’s the core of the Games, and I’m grateful that we get to witness it.

The pandemic has increased the potential for disaster: a positive test disrupts training; two years away from normal competition allows nerves to run amok; an empty set of stands throws off the sacred space. Many athletes are facing far bigger, deeper losses this year than these competitive concerns.

But all these challenges — from small and mundane to deep and soul-wrenching — increase the potential for triumph. When athletes make history, it’s not just because they’re the best performances. It’s because they’re the best performances set against the backdrop of astronomical pressures.

British distance runner Mo Farah tripped and fell in the middle of his 10,000-meter race in 2016, then came back for the gold. My own hero, diver Laura Wilkinson, won the 2000 women’s platform event with three broken bones in her right foot.

We love these athletes because things went wrong and they killed it anyway.

The game within the Games has always been about putting the right frame around the world, turning weaknesses into strengths.

For me, adapting as an athlete meant learning to love a crowd. For athletes this year, adapting means competing without one. The empty stands matter, as do all of the tolls of the pandemic.

But as usual, the winners will be those who overcome.

After competing in the 2012 Olympics, Cassidy Krug retired from diving and moved to New York City. Today she’s a freelance writer working on a book about elite athletes and retirement. Follow her on Twitter @cassidykrug.